The St. Charles Punch

This coming Saturday, May 15, as part of World Cocktail Week, Cure in New Orleans (one of my favorite bars anywhere) is holding an event called “Bartending by the Book” which will benefit the Museum of the American Cocktail and the New Orleans Culinary and Cultural Preservation Society. This’ll be an interesting event, because the Cure bartenders are holding themselves to follow classic recipes from one of the city’s most venerable imbibing tomes, Stanley Clisby Arthur’s Famous New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em, as difficult as that may be given the differences in ingredients between then and now.

Doubly interesting, as the creative bartenders at Cure tend to use the old recipes as jumping-off points rather than hew faithfully to them. At this event you’ll be in a bit of a cocktail time machine, sipping history as closely as we can get it.

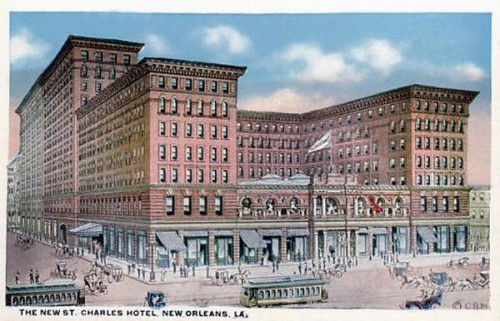

The four drinks they’ve chosen for this event include the familiar — the Daiquiri, the Stinger and the Vieux Carré — and one that might not be so familiar, although it’s local. That one’s the St. Charles Punch, named not for the grand streetcar- and oak-lined avenue stretching from Canal Street to the Riverbend, but for the grand hotel which once existed there. Or one of them, at least.

The St. Charles Hotel actually had three incarnations. The first one was designed by the architect James Gallier, whose name was given to Gallier Hall on St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans’ city hall from 1853 to 1958. It was the first truly grand hotel in the city, which was up until then not known for luxurious accommodations (nor for well-built ones, like the Planters Hotel, which collapsed into the soft soil in 1835, burying sixty people and killing a third of them)¹.

According to Mary Cable’s book Lost New Orleans, it was quite a sight:

The St. Charles was certainly no common structure. It was taller than any building in New Orleans — six stories, surmounted by a gleaming white dome that could be seen for miles up and down the river. According to Norman’s 1845 guidebook, “The effect of the dome upon the sight of the visitor, as he approaches the city, is similar to that of St. Paul’s in London.” Mr. Norman, beside himself with admiration, went on to speak of the “indescribable effect of the sublime and matchless proportions of this building upon all spectators — even the stoical Indian and the cold and strange backwoodsman, when they first view it, are struck with wonder and delight.”²

It wasn’t around long; “[t]his spendid pile lasted a bare fifteen years. In the spring of 1851 a fire that started in the kitchen spread through defective chimney flues and within three hours the entire hotel was in ashes.” Miraculously, no one was killed. Perhaps it was for the best; “according to a contemporary architect (not Gallier) the foundations had settled at least 28 inches, the external walls were cracked and the floors were ‘very undulating.'”³

A second hotel went up in the same spot, designed by Isaiah Rogers and George Purvis, very much like Gallier’s Greek revival original but without the great dome. It opened a mere two years later and was itself burned to the ground in 1894.

Third time’s a charm … the third St. Charles Hotel went up on the same site two years later in 1896 and was quite a nice hotel, albeit without the grandeur of its predecessors.

For about sixty years it was a New Orleans favorite for Mardi Gras balls, coming-out parties, high-level political meetings and as a rendezvous for the elite, to whom it was the equivalent of New York’s old Ritz-Carlton. For no imperative reason, the third St. Charles was demolished in 1974. The ghosts of three memorable buildings now hover above a parking lot.4

According to Arthur this punch was a specialty of the bar at the St. Charles Hotel (presumably the third) and was in great demand among its patrons. I’m not sure it’s technically a punch, as the proportions are nowhere near the classic “1 of sour, 2 of sweet, 3 of strong and 4 of weak, plus spice.” There’s not much weak in here, no spice and it’s a very tart punch.

That said, it’s a delightful punch and goes down … dangerously quickly.

THE ST. CHARLES PUNCH

(adapted from Stanley Clisby Arthur’s

Famous New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em)1 teaspoon rich simple syrup (2:1)

1/3 teaspoon orange curaçao (1 dash)

1-1/2 ounces fresh lemon juice

1-1/2 ounces ruby port

1 ounce CognacArthur’s original instructions: “Dissolve the sugar with a little water in a mixing glass. Add the lemon juice, the port wine, the Cognac, and last the curaçao. Fill the glass with fine ice and jiggle with the barspoon. Pour into a long thin glass, garnish with fruit, and serve with a straw. […] Don’t omit the straw; this drink demands long and deliberate sipping for consummate enjoyment.”

I loved Anita‘s comment from the photo’s Flickr page: “Any drink that looks that good can demand pretty much anything it likes.”

I did without the original teaspoon of granulated sugar and splash of water, and substituted a rich simple syrup for ease of use. I also upped the curaçao to a teaspoon so it wouldn’t get lost — I am a fan of dashes of ingredients in cocktails, but I wanted the orange flavor to be a bit more there, and a tad more sweetness to counter the lemon. I also used cubed ice in the photo because I’m a lazy bastard. Don’t be like me — crush your ice!

1. Mary Cable, Lost New Orleans (New York; American Legacy Press, 1980), pp. 108-109.

2. Ibid., p. 109.

3. Ibid., p. 111.

4. Ibid., p. 114.